On Chhenna

The Portuguese Contribution to Indian Sweets

Ask any well-informed Indian foodie about Indian sweets that owe their origins to a foreign land, and chances are, they’ll mention sweets like jalebi, gulabjamun, or halwa, all of which are descended from very similar desserts in the Middle East. Sweets that came to us from Central Asia, along with a plethora of savoury dishes, and which—like the kebabs, biryanis, naans, qormas, etc—stayed on.

But what about Indian desserts that owe something to Europe? After all, India has been colonized, for substantial lengths of time, by various European countries. The British, the French, and the Portuguese ruled parts of the country (the British pretty much most of it, even if that rule was de facto and not de jure) for more than two hundred years each.

There are Indian sweets that definitely owe something to the British (and not just the gulabjamun-like Lady Canning/ledikeni, invented in honour of the vicereine). Shahi tukda, for instance, which uses sliced bread, introduced by the British. It’s a different matter that a very similar dessert, known as aish-el-saraya, consisting of syrup-soaked toast topped with thickened sweetened milk, is made in the Middle East as well. Perhaps the original ‘bread’, when the dessert first made its way to India, was something rather like a fluffy tandoor-baked bread, and was later replaced in both India and the Middle East with the more convenient sliced bread?

Anyhow. I doubt if many people, even devoted mithai-eaters, would realize what a major part the Portuguese played, even if inadvertently, in the realm of Indian sweets. Specifically, the chhena-based sweets of Bengal.

The ancient Indian ethos around food decreed that milk had a special status: as food historian KT Achaya explains in his book Indian Food: A Historical Companion, “…milk as it emerges hot from the udder is already a cooked food in ritual terms, having been cooked within the animal by the divine power of Indra.” To deliberately curdle milk by adding an acid to it—as happens in the production of chhenna or paneer—would be ritualistically taboo for this reason (note that thickening milk by long cooking, which produces khoya, was considered above board). Achaya mentions some ancient or medieval sweets, made both in Bengal and outside, which resemble modern-day sandesh, but remarks that these were probably made from khoya rather than chhena. There are other theories, though, which suggest that curdling milk was by no means unknown in ancient India.

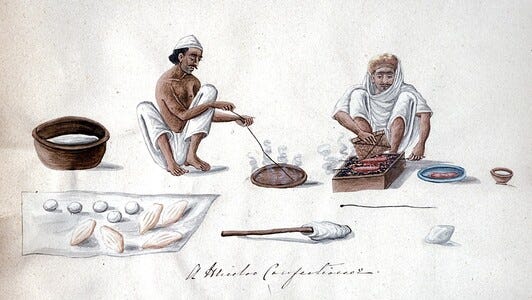

Emily M.S. Anoul, Hindu confectioner and potter.

Courtesy Wellcome Collection, Wikimedia Commons

The Portuguese had begun making inroads into Bengal in the early 16th century, but it wasn’t until 1575 that, permitted by Akbar to set up a factory at Hooghly, they established a large settlement here. It wasn’t long before they began to introduce their own foodways, creating familiar foods: baking European-style bread, for instance; and making fruit preserves. And, of course, making cheese. Portuguese attempts at cheesemaking in Bengal ended up in a rather unique smoked cheese (the artisanal Bandel cheese, now hopefully soon to get a GI tag): unlike European cheeses, which require the milk to be curdled with the use of rennet, Bandel cheese is made by curdling the milk with acid.

Bandel cheese. Wikimedia Commons; By Rangan Datta Wiki - Own work,

CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=102703673

… which basically means that chhenna is created. As Achaya explains in his book, there are two types of chhena: a looser, softer version that’s made by curdling milk with whey, and a firmer, grittier form made with the use of lime juice. While the Portuguese were more interested in taking the resultant chhena a few steps further along and turning it into cheese, local sweetmakers saw the opportunity to use the chhena in other, more interesting ways… and an array of sweets was born.

Interestingly, several of Bengal’s most famous sweets have well-documented origin stories, so to say. In circa 1760, for instance, a confectioner named Madhusudan Pal, in Natore (now in Bangladesh) found a way to use leftover chhena: by mixing it with syrup and then boiling the lot. Because the chhena was ‘kaacha’ or raw (untreated) before it was cooked with the syrup, the resultant sweet was called kaachagolla.

The rasogolla has rather more of a disputed origin, even though many believe that it was invented by a man named Nabin Chandra Das in 1868. Several food historians, however, subscribe to the theory that rasogollas were already around; Nabin Chandra Das only refined the sweet and made it more of a commercial success. As if that wasn’t complicated enough, neighbouring Odisha has its own claims to the rasogolla, with local religious belief plugging the kheer mohana (a version of the rasogolla) as a favourite food of the goddess Lakshmi, and offered to her from as far back as the 12th century CE.

Who knows? As you can see throughout this piece, there’s a lot of this-not-that, this-or-that, surrounding Bengali sweets. Did the Portuguese inadvertently give us chhena, or did we already use it? Did Nabin Chandra Das invent rasogollas, or not? Are rasogollas even Bengali?

There’s a Hindi proverb, aam khaane se matlab, ped ginne se nahin: to concern oneself with eating the mangoes, not counting the mango trees. That is my motto when it comes to Bengali chhena-based sweets. Enjoy them, don’t worry yourself about their antecedents.

Interesting !